The Teen Mental Illness Epidemic Began Around 2012

This is not just "Kids these days"

From the first time I wrote about Gen Z in 2015 (with Greg Lukianoff, in our Coddling essay) through my most recent discussion in a December interview with Tunku Varadarajan in the Wall Street Journal, the main criticism I have heard is that I'm just another old man (I'm 59) shaking his fist and complaining about "kids these days," when in fact "the kids are alright." If that's true, then the first half of the Babel project—on what social media did to childhood and to teen mental health—is fatally flawed. Is the criticism valid?

1. The Case Against Me

Two responses to that WSJ essay do us the favor of collecting quotations from previous generations complaining about the behavior of youth. First, see this Twitter thread from Paul Fairie, titled A Brief History of Kids Today Are Spoiled

Fairie includes this 1925 gem:

Remove the girl or boy of today from radio, the telephone, furnace heat, the automobile, the libraries, movies, and other forms of amusement and comfort––give them merely a jackknife and nature's unchanging wonders for amusement, and how would they fare? … Ennui would claim them for its own and … they would fare ill until returned to their accustomed habitat of convenience and plenty.

Second, see this essay by Mike Males in LA Progressive, titled Enough Youth-Bashing, which includes this:

From Greek poet Hesiod to modern youth bashers led by psychology professors Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge and former first lady Michelle Obama, no one says anything new. Hesiod cornered the market with his "no hope for the future of our people" rant against the "reckless… frivolous youth of today" (700 BC).

And this:

Eon after eon, it's the same float going by. Socrates thought books made the young mentally weak. Panics over coffee, witches, jazz, dime novels, comics, TV, backwards-masked lyrics, Ozzy, Eminem, Tupac, Grand Theft Auto, Harry Potter's Hermione, Miley, cellphones, Facebook, sexting, social media… the endless ephebiphobic idiocies should be retitled, "I'm Superior!" and given their own dismal library shelf.

These critics make two valid points: First, you can find these criticisms in all recent generations and in some going back thousands of years.1 Second, the criticisms are often part of a larger moral panic that arises in response to any new consumer product––and especially any new technology––that "kids these days" are using. Social media clearly fits this pattern. (Robby Soave explained the dynamics of tech panics well in his 2021 book Tech Panic.)

The critics also gain support from empirical studies by psychologists John Protzko and Jonathan Schooler, whose 2019 essay in Science Advances was titled Kids these days: Why the youth of today seem lacking. Protzko and Schooler summarize their many studies showing that older people suffer from a variety of cognitive biases, such as that we each have biased and self-serving memories of what we were like at that age, and so we older people always find current younger people inferior and declining.

In sum, it's reasonable to start with skepticism of my claim (with Jean Twenge) that there is an epidemic of mental illness that began around 2012, and that is related in large part to the transition to phone-based childhoods, with a special emphasis on social media. It makes sense to embrace as a null hypothesis the skeptics' view that there is nothing to see here, just another moral panic, and the kids are fine. I am in full agreement that the burden of proof falls on me.

But if you take that as your null hypothesis, then you should be open to evidence that the null hypothesis is false and this time is different. Anecdotes about kids who began cutting themselves the week after going on Instagram won't do. You'll want to see peer-reviewed studies and high-quality surveys showing 1) that there is in fact an epidemic of mental illness and 2) that phones and social media are substantial contributing causes. I am currently writing a book that makes both of these arguments: Kids In Space: Why Teen Mental Health is Collapsing.

In the rest of this Substack post, I offer a preview of the evidence that a mental illness epidemic emerged around 2012. I won't directly address the issue of causality here. I'll do that in many future posts, and in the book. (You can find a short version of the argument in my 2022 Senate testimony.) This post simply responds to the "kids these days" critics. I make the case that this time really is different. The kids have not been alright since the early 2010s.

2. The Collaborative Review Doc

I have been collaborating with Jean Twenge (author of iGen, and the forthcoming Generations) and Zach Rausch (my research assistant) on a pair of collaborative reviews that are open-source Google documents where we collect all the evidence we can find, on both sides of each question, and we invite critics to add comments and studies. In this post, I present our document titled: Adolescent mood disorders since 2010: A collaborative review. In future posts on this Substack, I'll present many more collaborative review docs and explain why open-source Google docs are an essential adjunct to social science research, especially regarding social trends that are changing too fast for the slow gears of academic life to keep up with––phenomena like social media and its effects on teen mental health and on liberal democracy.

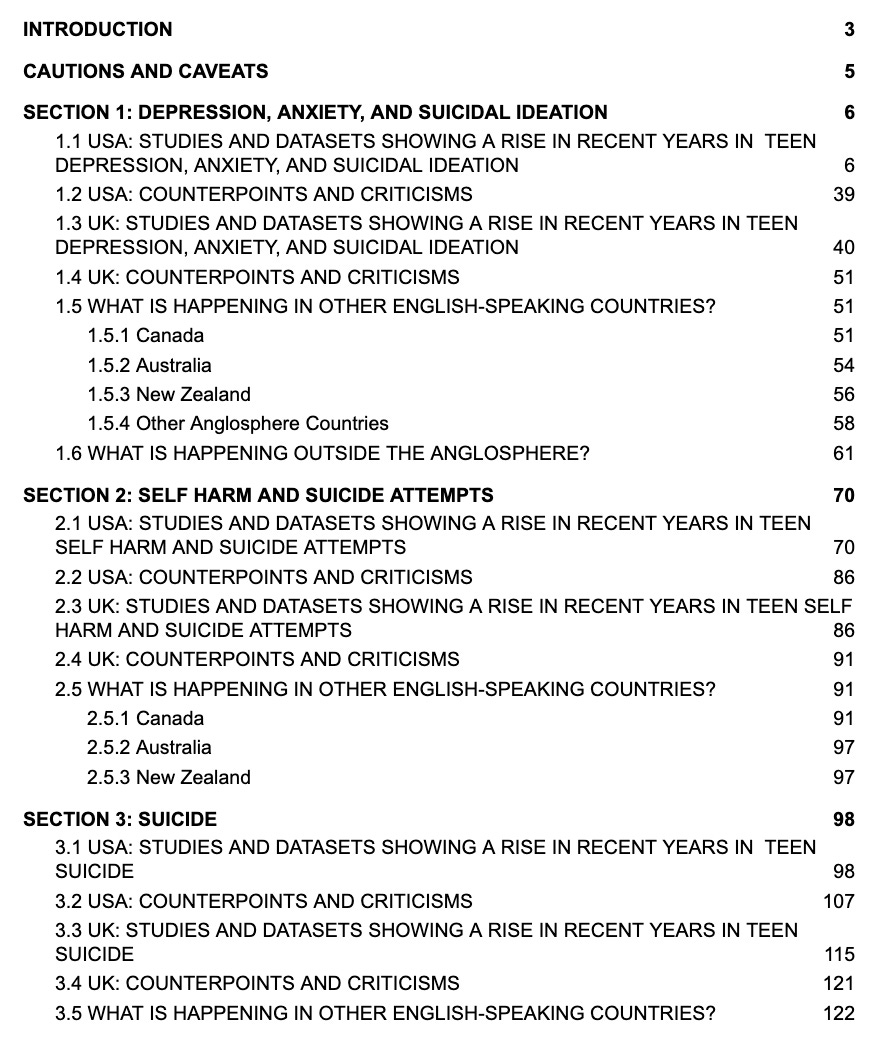

Here is the first half of the Table of Contents, to give you a sense of the layout. Please look around the doc itself. If you are a researcher or mental health expert, ask for commenting rights to add your own studies and criticisms. I am a devotee of John Stuart Mill who wrote that "he who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that." Help me get this right.

Figure 1. The first part of the Table of Contents from Adolescent mood disorders since 2010: A collaborative review.

First, let's look at what Gen Z says about its own mental health, compared to previous generations. After that, we'll look at hard evidence about behavior, to address the criticism that the only thing that has changed is Gen Z's willingness to report their mental health problems.

3. Increases in Self-Reported Depression and Anxiety

Section 1 of the Collaborative Review summarizes self-report surveys that have been conducted at regular time intervals since 2010 or earlier. Do members of Gen Z say that their mental health is declining? Yes, in every study we can find. We cannot find any studies on the other side. I will focus today's post on data from the United States. I'll have a future post on what's happening internationally, showing that the same patterns are happening in largely the same way at roughly the same time in Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, and I'll share with you what Zach and I are learning about other countries beyond the Anglosphere.

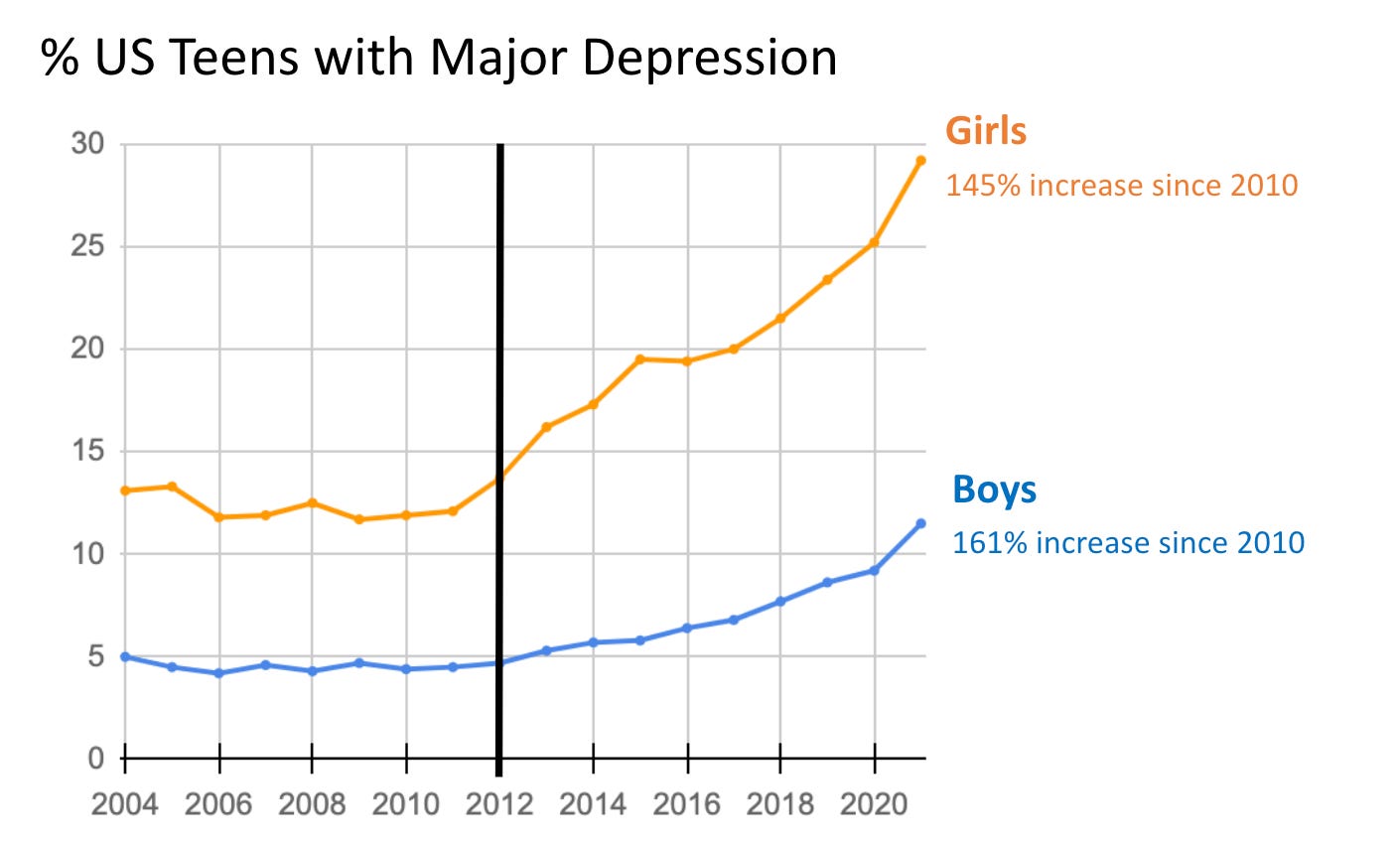

Here are two of the graphs you'll find in section 1 of the Collaborative Review document:

Figure 2. NSDUH data, graphed in 1.1.2 Twenge, Cooper, Joiner, Duffy, & Binau (2019), and re-graphed with more recent data by Haidt. Currently on p. 12 of the Collaborative Review doc.

As you can see in Figure 2, and in most of the Figures in the review doc, there was no sign of a problem before 2010, and the epidemic is well underway by 2015. You can also see that the rate of depression is much higher in girls, as is the absolute increase (since 2010 an additional 18% of girls suffered from depression in 2021, compared to an additional 6% of boys), however, the relative increase is similar in both sexes: around 150%. The rate had more than doubled before the covid epidemic. The 2020 data were collected in early 2020, just before covid restrictions, and the 2021 data were collected a year later before vaccines were widely available.* You can see that covid accelerated the rise in depression in that last year, but it was already rising really fast.

[*Correction, from Jean Twenge, added 2/15/23: It's the Monitoring the Future 2020 data that was all collected before the pandemic hit, not the NSDUH data, which was collected in both Q1 and Q4 of 2020. Either way, covid seems to have only added a bit of acceleration to a rapidly rising trend line]

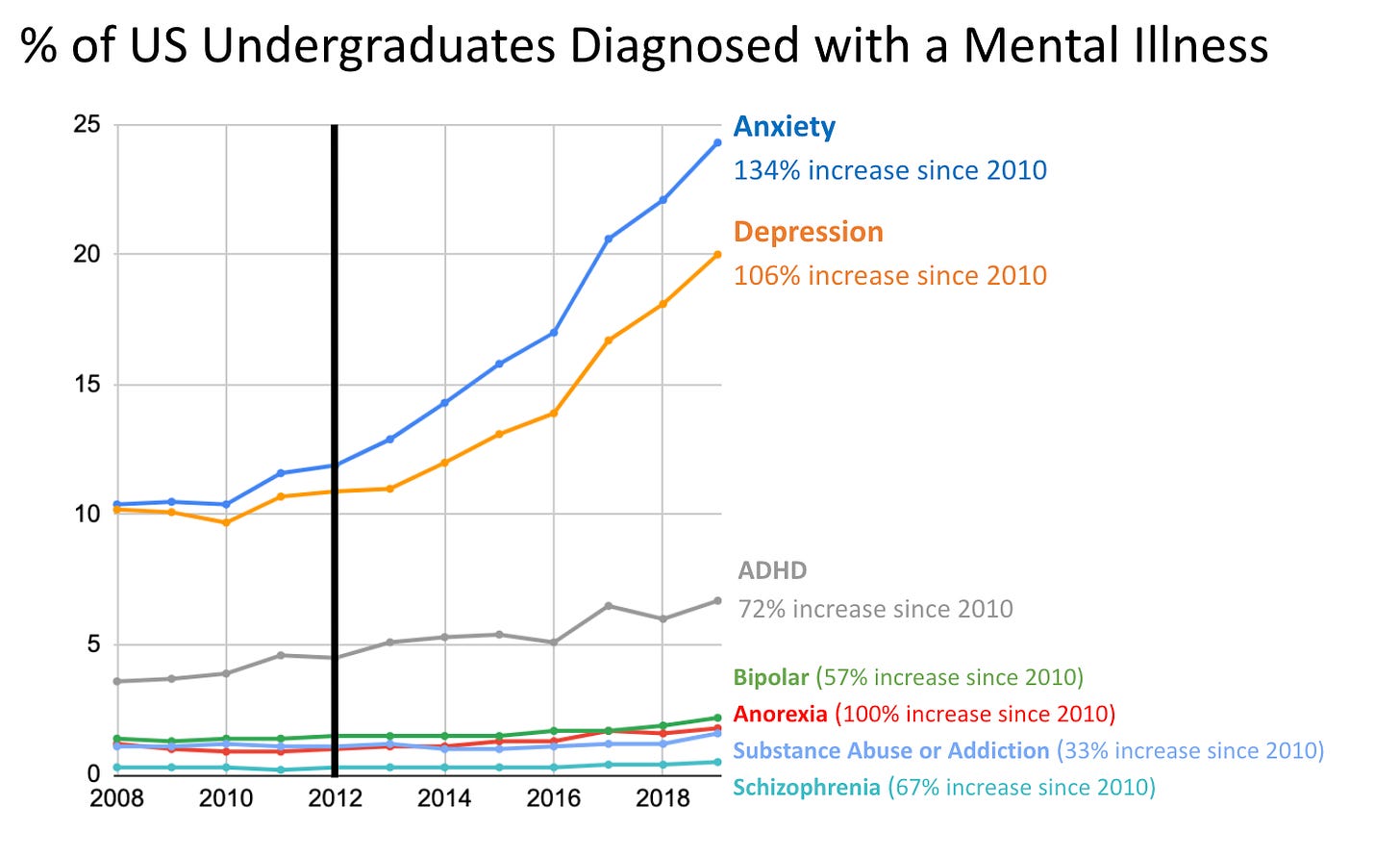

Figure 3. American College Health Association (2019), National College Health Assessment. Study 1.1.17, currently on p. 36 of the Collaborative Review doc.

Figure 3 comes from a very different source: the mental health clinics on hundreds of college campuses. You can see once again that there's not much to see before 2010, but the epidemic is in full gear by 2015. You can also see that while rates of all disorders have increased, the increases are largest, in both relative and absolute terms, for mood disorders, a class of mental illness that is made up primarily of depression and anxiety disorders (which includes anorexia). In 2019, just before covid, one in four American college students suffered from an anxiety disorder, compared to just one in ten back in 2010. The rate may be higher today.

Section 1 of the collaborative review shows that according to the kids themselves, the kids are not alright. What happens when we ignore what they say and look at what they do?

4. Increases in Self-Harm

In 2019, when Twenge and I launched the document, there were still some skeptics who argued that the large increases you see in Figures 1 and 2 reflect only a change in Gen Z's willingness to disclose their struggles, which is a good thing. Here is psychiatrist Richard Friedman, in the New York Times in 2018:

"Despite news reports to the contrary, there is little evidence of an epidemic of anxiety disorders in teenagers… There are a few surveys reporting increased anxiety in adolescents, but these are based on self-reported measures — from kids or their parents — which tend to overestimate the rates of disorders because they detect mild symptoms, not clinically significant syndromes."

This argument is heard less often nowadays, but it was made by one critic recently in response to my WSJ interview. Here is Vicki Phillips, in Forbes, in an essay titled Gen Z: Hopeless Or Hopeful?

[Haidt] fails to note the remarkable truth. Gen Z is in fact embracing a new, more open and honest relationship with their mental health, one that destigmatizes the issue so that it can be addressed. This is leading to more people reporting their mental health challenges and seeking support, and contributing to the rising numbers of reported cases. More effective diagnoses and increased connection to care are both good by any measure. As an educator, I feel an obligation to support Haidt on his personal learning journey. And as someone who has actually worked with Gen-Zers, I can tell you, the kids these days are more than alright.

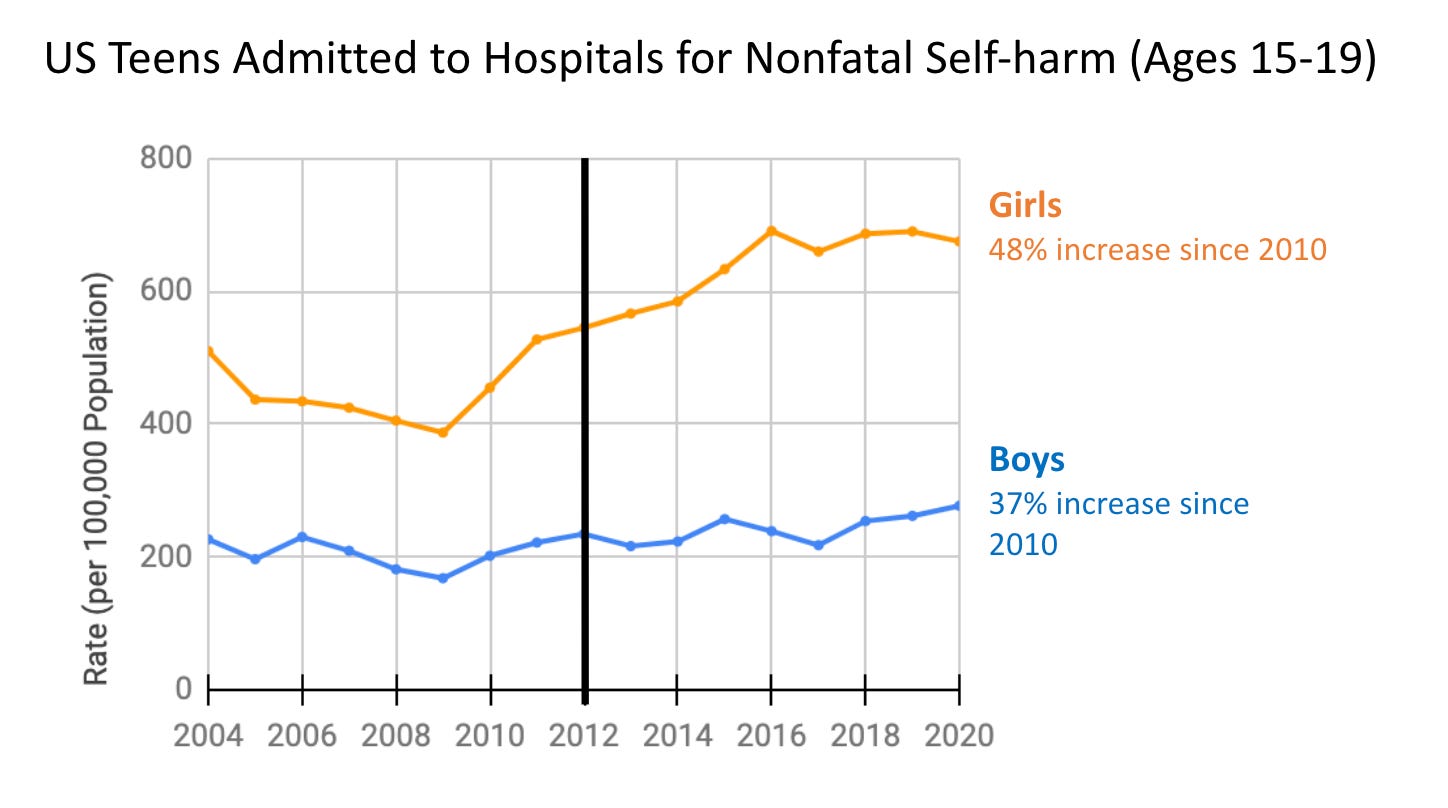

But if Phillips and Friedman were correct that "the kids are alright" and the appearance of an epidemic is an illusion based on Gen Z's "more honest relationship with their mental health," then we would not see any change in objective measures of mental health, such as hospitalizations for self-harm, or deaths by suicide. But in fact, we do see such changes, and the timing and magnitude of them generally match the changes in self-reported mental health problems. Sections 2 and 3 of the Collaborative Review doc report these findings.

Figure 4. Hospital admissions for self-harm, older teens (ages 15-19), CDC data. See section 2.1.1 of the collaborative review doc.

Figure 4 shows the number per 100,000 older teens who are admitted each year to hospitals because they harmed themselves, mostly by cutting themselves with sharp objects. Once again there is no sign of a problem before 2010, and the epidemic is raging by 2015.

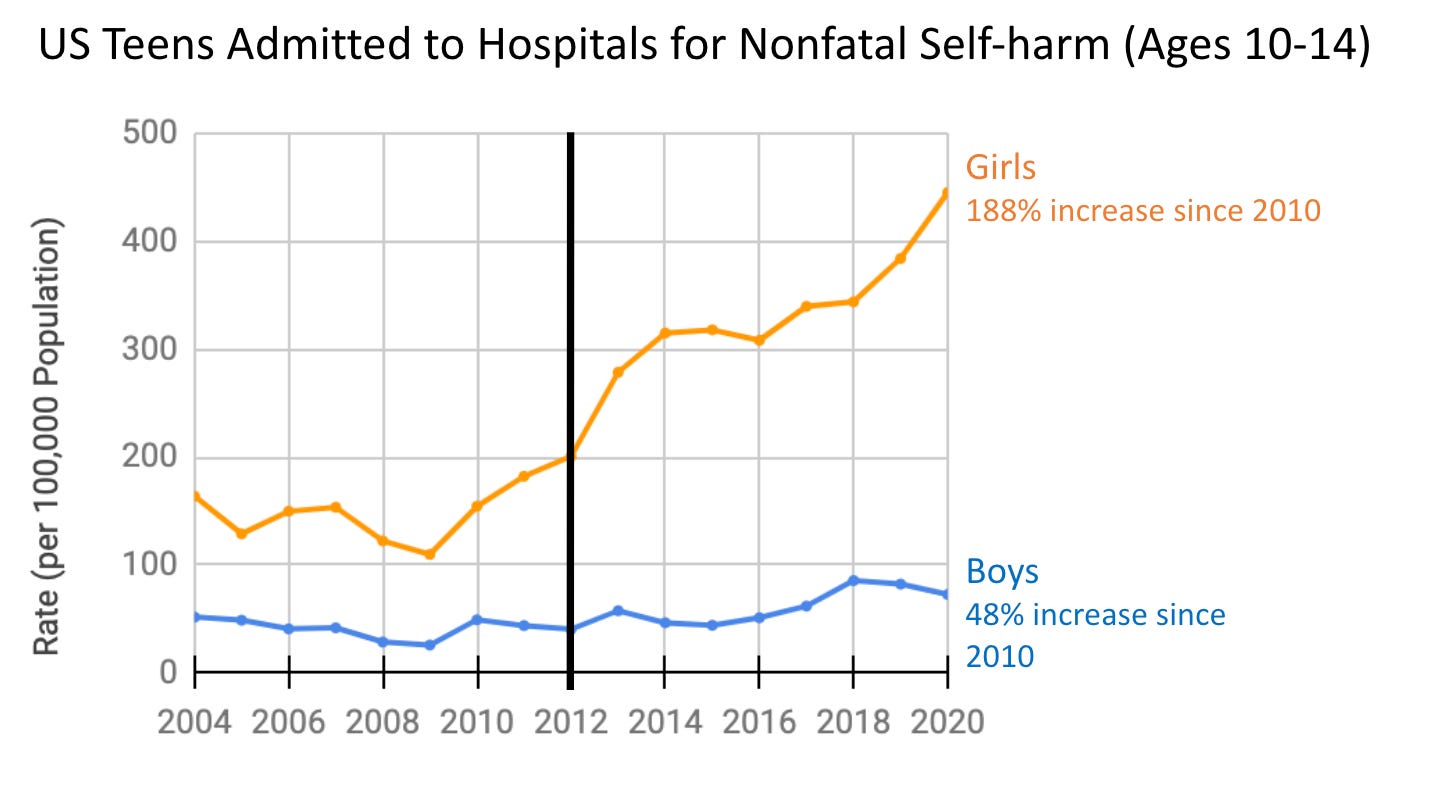

Figure 5. Hospital admissions for self-harm, younger teens (ages 10-14), CDC data. See section 2.1.1 of the collaborative review doc.

Figure 5 is the same as Figure 4 except that it shows what happened to younger teens, ages 10-14. Younger teens were very rarely hospitalized for self-harm before 2010, but by 2020 the rate for girls had nearly tripled, rising to exceed the rate at which older teen girls were hospitalized back in 2009. This is a clue as to what caused the epidemic. What could have changed right around 2012 that hit tween and young teen girls hardest? (I'll answer that in a later post.)

5. Increases in Suicide

Section 3 of the Collaborative Review doc presents the most tragic data of all: a large increase in the number of completed suicides.

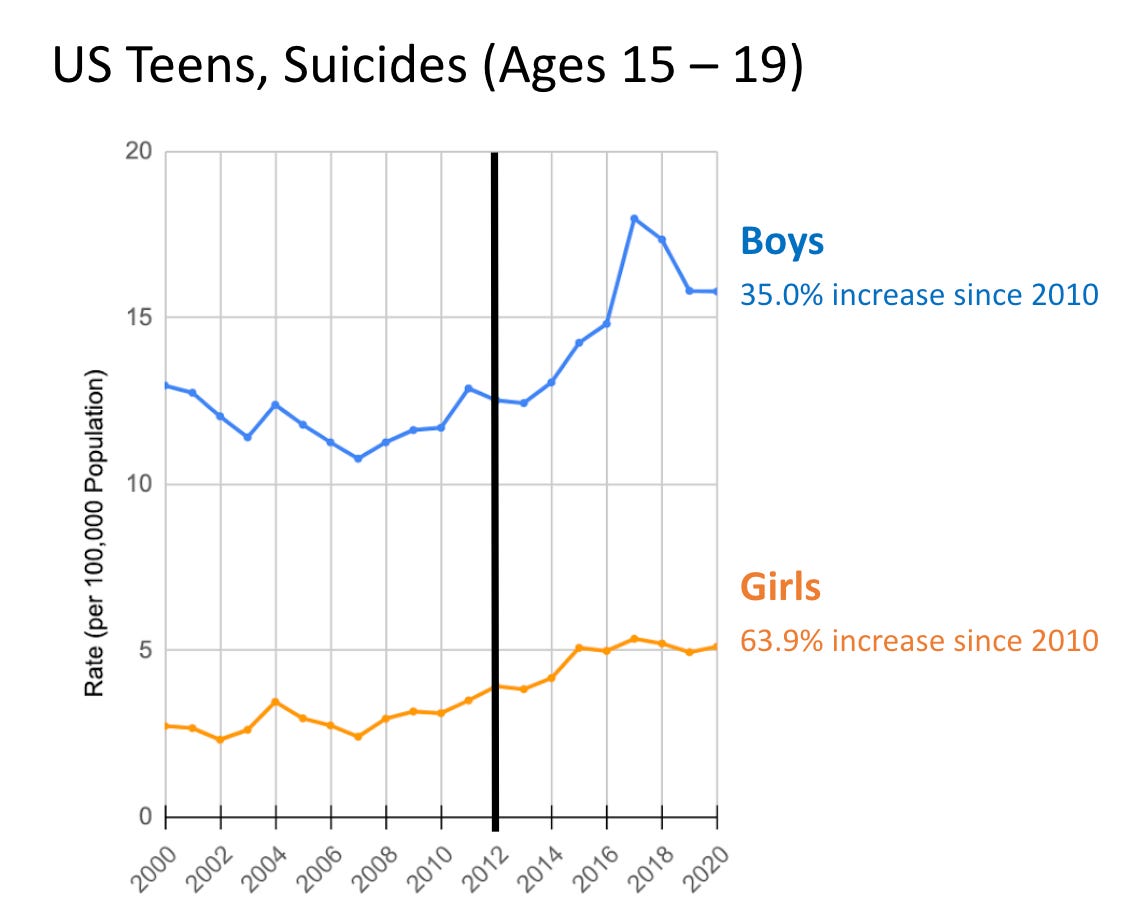

Figure 6. Suicide rate per 100,000 of US population, ages 15-19. Source: CDC, See section 3.1 of the Collaborative Review.

For suicide, the rates are always higher for boys and men. Girls and women make more suicide attempts, but they are more likely to use reversible means. Boys and men are more likely to use firearms and tall buildings, which are not reversible. Suicide takes a much larger toll on boys and men. But it is noteworthy that the relative increase since 2010 is larger for girls and women.2

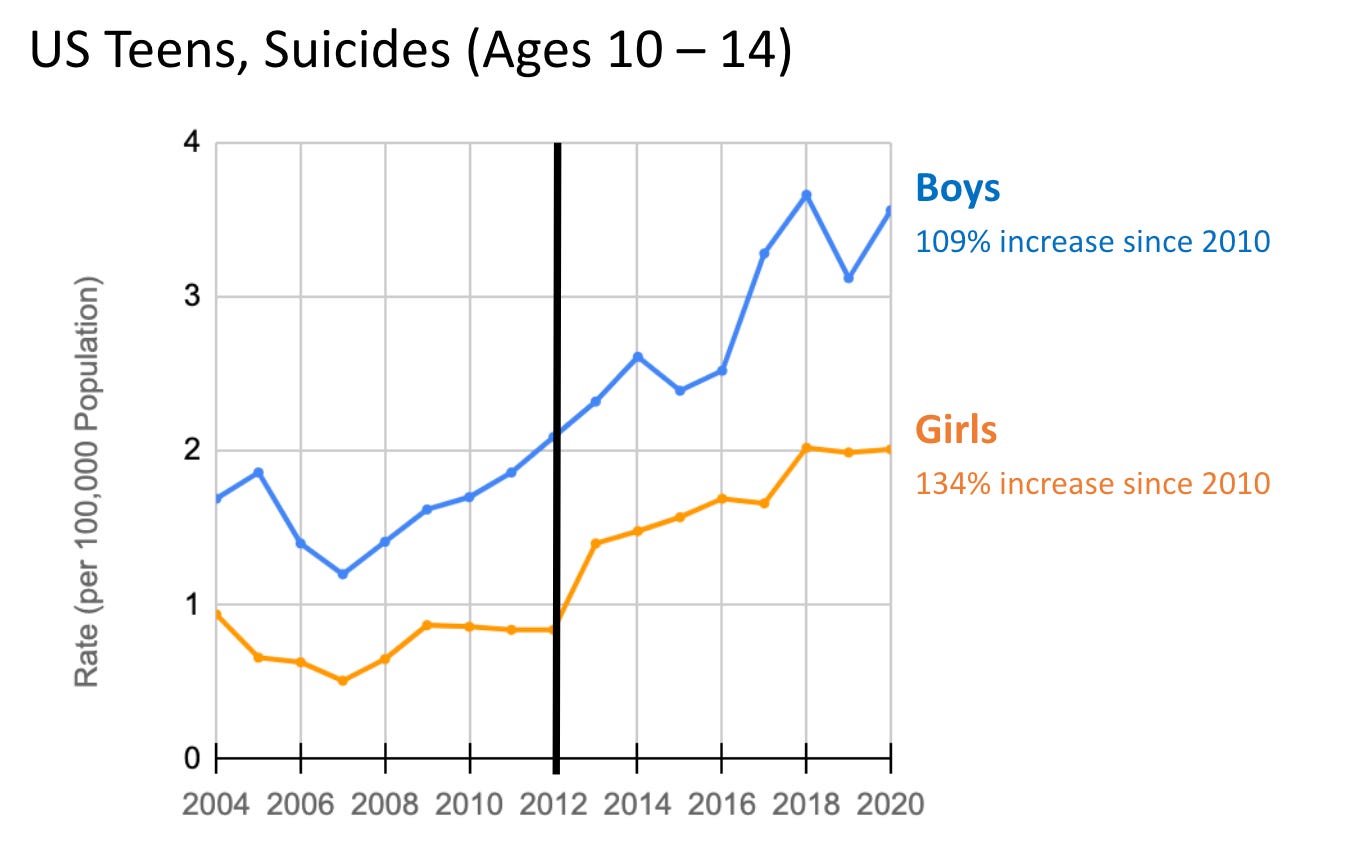

Figure 7. Suicide rate per 100,000 of US population, ages 10-14. Source: CDC, See section 3.1 of the Collaborative Review.

When we look at the change in suicide rates for tweens and younger teens, in Figure 7, we find three features that echo what we saw in the graphs for self-harm: 1) the percent increase is larger for girls than for boys, 2) the percent increase for young girls is much larger than the increase for older girls, and 3) even more than in Figure 4, there is a sharp increase for girls between 2012 and 2013. In fact, there was a 67% increase in suicides in that single year. This sudden and enormous spike, in a single year, once again forces us to ask: what changed in the lives of 10-14 year old girls in 2012?

6. Conclusion

I began this essay by taking the burden of proof upon myself. Given the long history of tech panics, you should come to this question and this blog with skepticism. Your default assumption should be the null hypothesis so often asserted by my critics: this is just one more unjustified freakout by older people about "kids these days."

But as I have shown in this post, the evidence that this time is different is very strong. In 2010 there was little sign of any problem, in any of the long-running nationally representative datasets (with the possible exception of suicide for young teen boys). By 2015––when Greg Lukianoff and I wrote our essay The Coddling of the American Mind––teen mental health was a 5 alarm fire, according to all the datasets that Jean Twenge and I can find. The kids are not alright.

Please join me on the After Babel Substack to figure out why. In future posts I'll cover topics including these:

What is happening to teen mental health in other countries? Is this just an American thing?

What is the evidence that the epidemic is caused in large part by social media?

What is the evidence that the loss of free play and risky play contributed to the epidemic?

What is happening to boys? They're not on social media as much, so why is their mental health deteriorating too?

Nuances and complexities

I started this Substack to help me write two books, as explained in the About post. In many posts, such as this one, I'll make a strong assertion in the title of the post in the hope of drawing criticism. Did the epidemic really start in 2012, or was it earlier? Was it gradual, not a sharp bend in 2012? I want to hear all of the counterarguments and find all of the contrary evidence now, rather than waiting until after the book is published. So please be (constructively) critical in your comments. It is so hard to find time to write the books that I won't be able to respond to comments one by one, but I will read them all and I'll pull out the best criticisms and respond to them in new text at the bottom of this post.

It is beyond the scope of this short post to go into variations by race, SES, ideology, and other factors, but I have done so in Appendices A through G of the collaborative review doc. TLDR: there are some variations, such as that the increases in depression and anxiety were larger among sexual minorities, and among girls who self-identified as liberal. But the general trends are similar across all groups.

The suicide rate for boys was higher in the 1980s than it is now. I believe those earlier levels, which used to rise and fall with the violent crime rate, were caused in part by the high and rising prevalence of lead in children's bloodstreams from the 1950s until leaded gas was banned in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Rates of suicide and violence then plummeted 15 years later, and sociologists have not yet converged upon an explanation. You can see graphs of these changes, and find arguments on both sides, in my debate with Chris Ferguson, in section 3.2.1 of the Collaborative Review doc.

Responses prompted by comments

See responses in post #2: The new CDC report shows that Covid added little to teen mental health trends.

Some of the quotations attributed to Ancient Greek sources may be inaccurate, but once Western societies began the modernization process in the 17th century and cross-generational change sped up, the quotations seem to increase in frequency. (You can find many more here).

latifat olatunji

ReplyDelete