Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic in Teen Girls. Here's the Evidence.

Journalists should stop saying that the evidence is just correlational

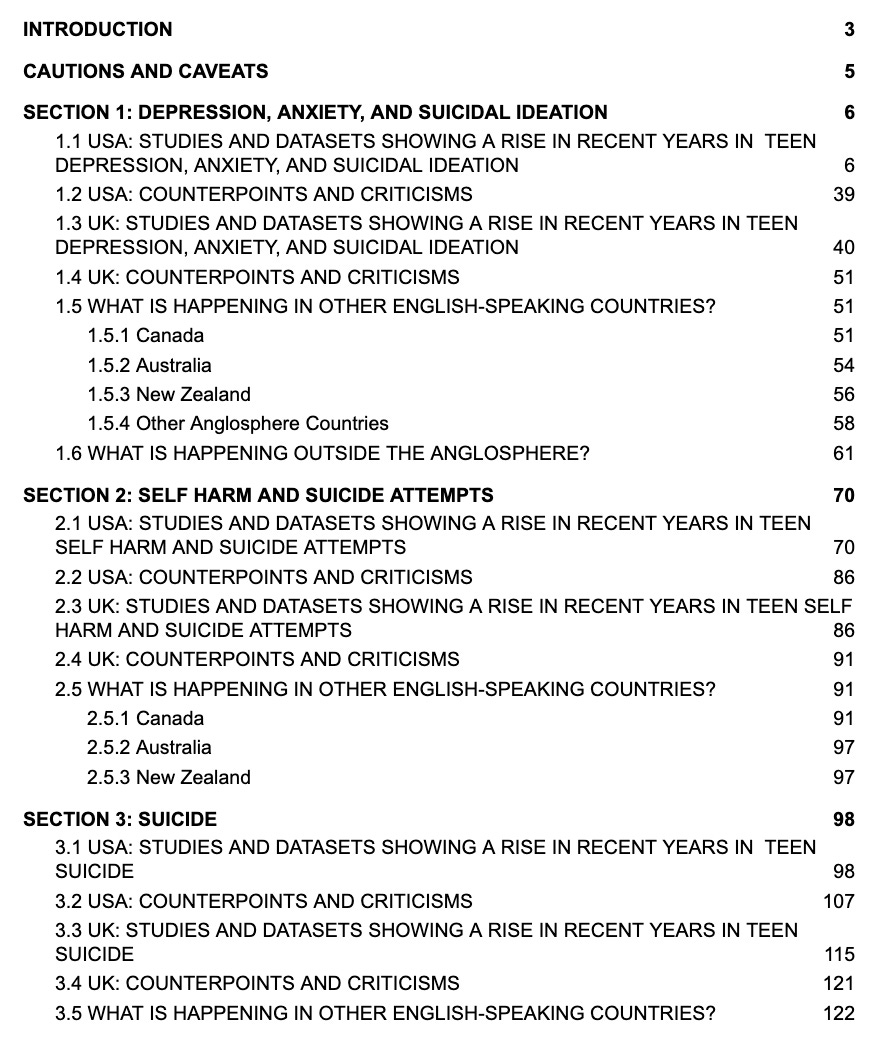

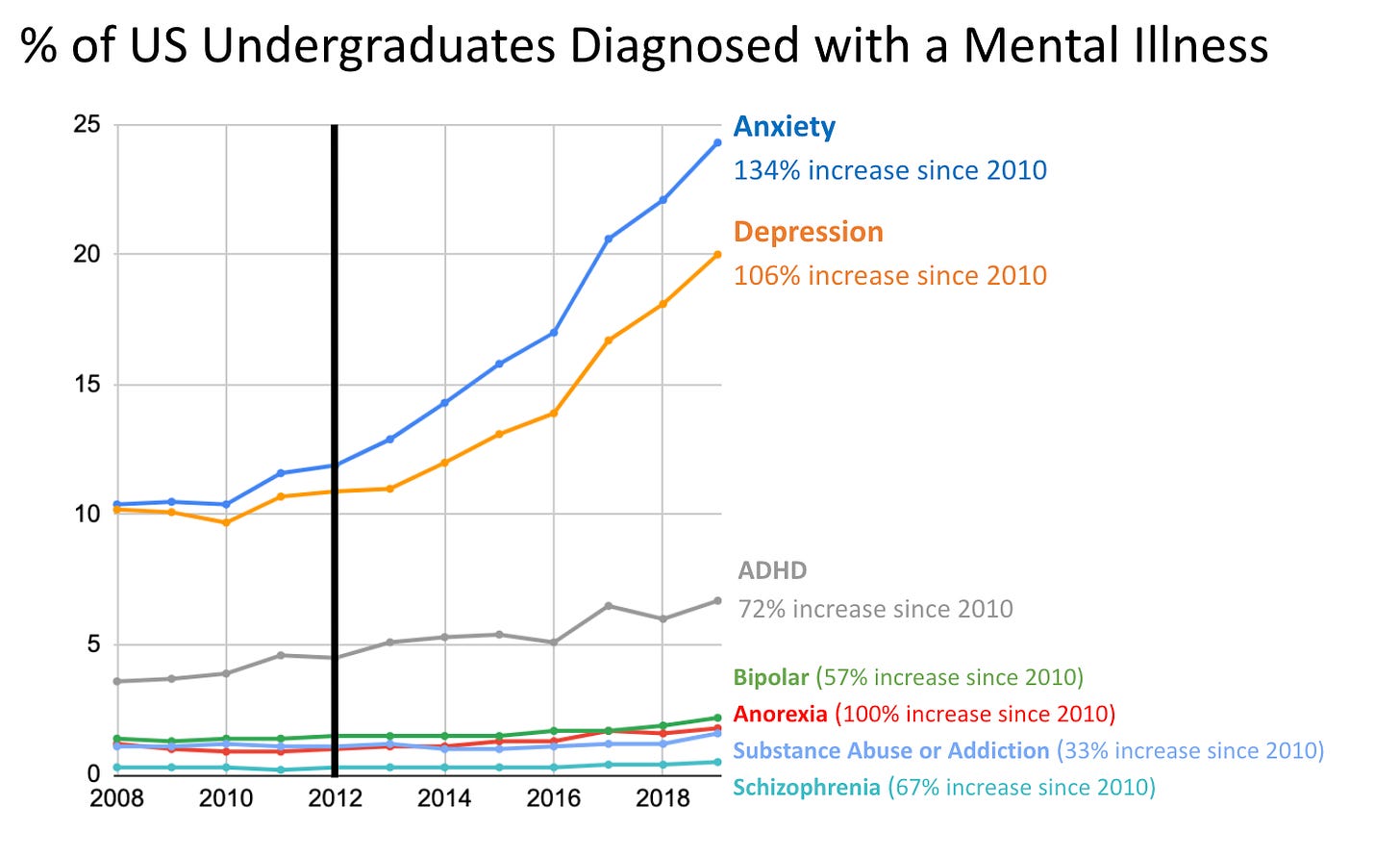

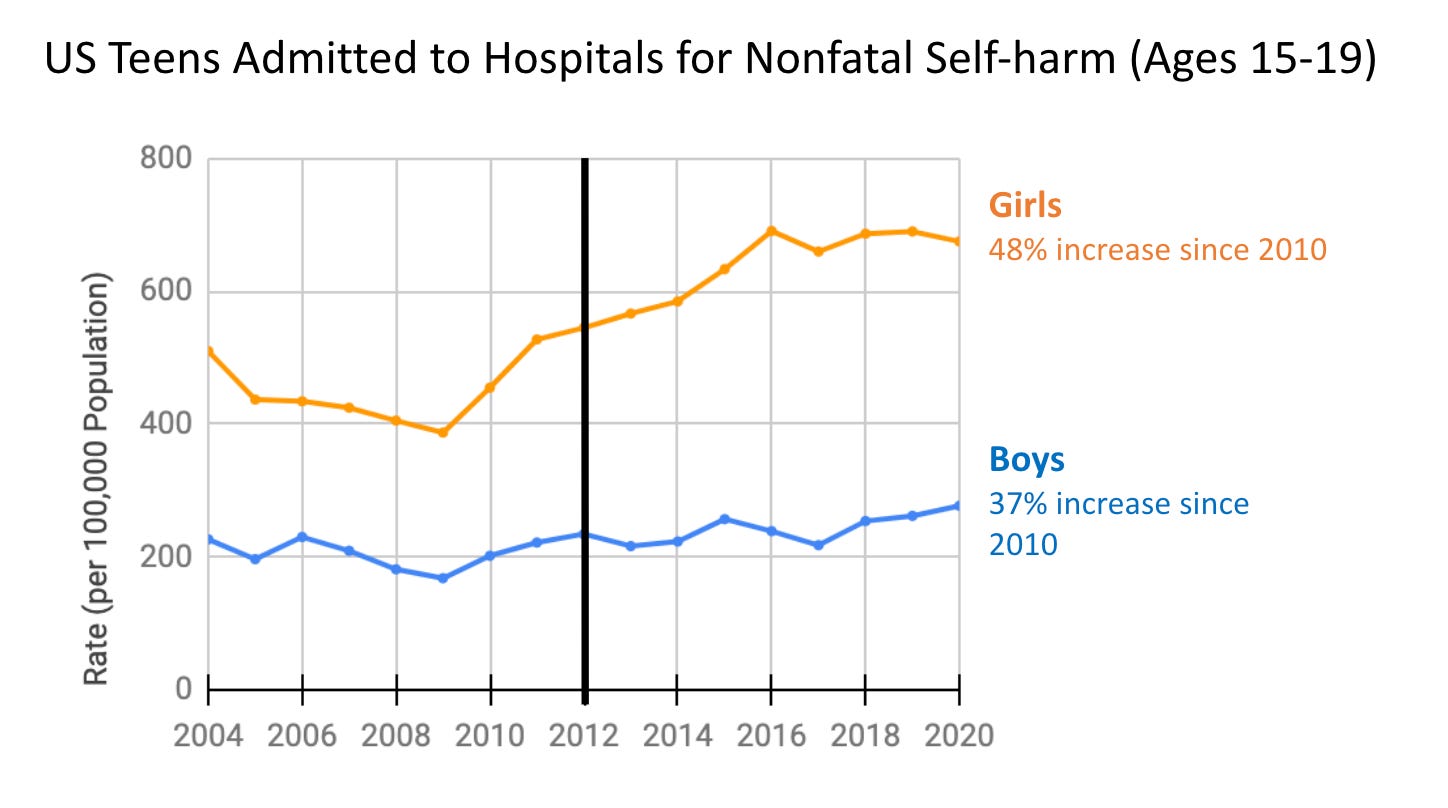

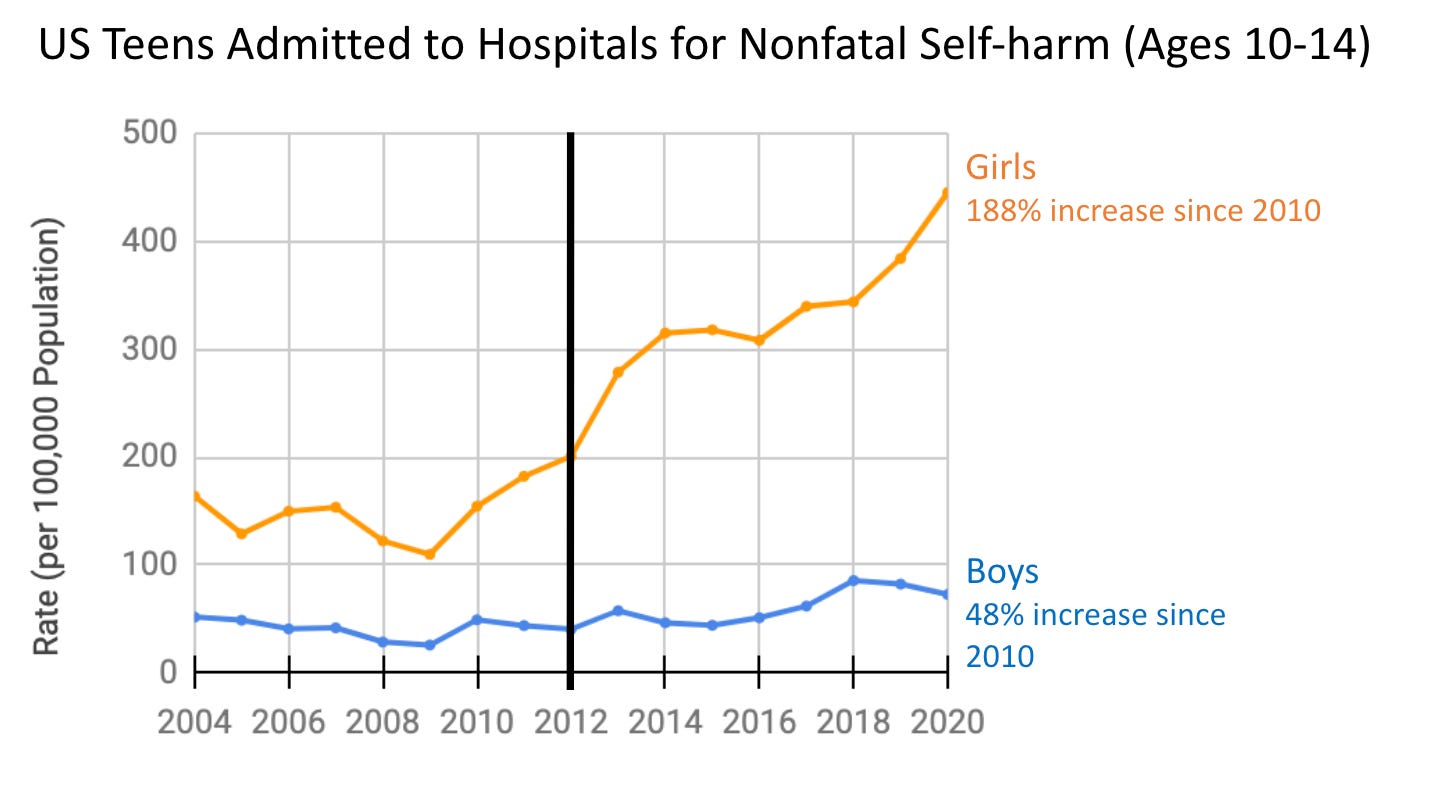

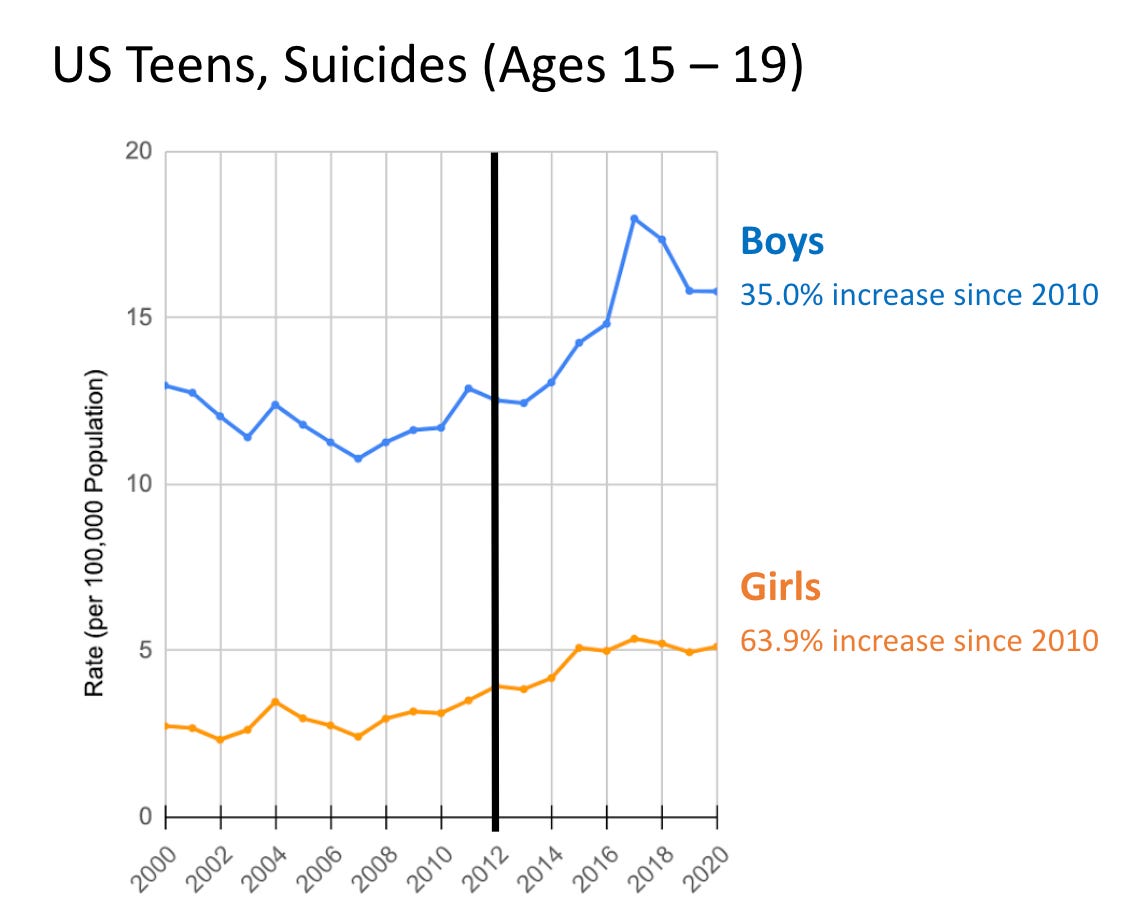

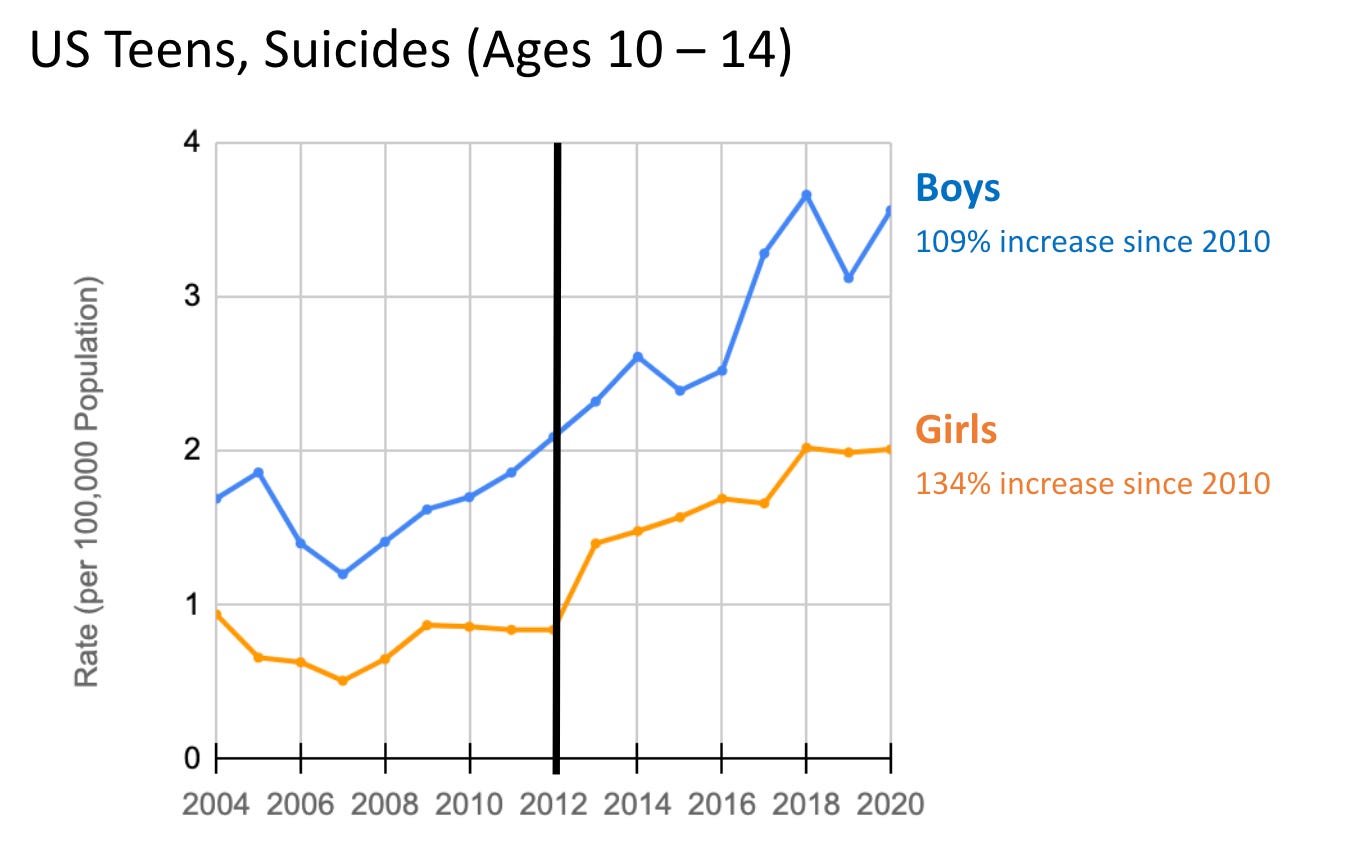

A big story last week was the partial release of the CDC's bi-annual Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which showed that most teen girls (57%) now say that they experience persistent sadness or hopelessness (up from 36% in 2011), and 30% of teen girls now say that they have seriously considered suicide (up from 19% in 2011). Boys are doing badly too, but their rates of depression and anxiety are not as high, and their increases since 2011 are smaller. As I showed in my Feb. 16 Substack post, the big surprise in the CDC data is that COVID didn't have much effect on the overall trends, which just kept marching on as they have since around 2012. Teens were already socially distanced by 2019, which might explain why COVID restrictions added little to their rates of mental illness, on average. (Of course, many individuals suffered greatly).

Most of the news coverage last week noted that the trends pre-dated covid, and many of them mentioned social media as a potential cause. A few of them then did the standard thing that journalists have been doing for years, saying essentially "gosh, we just don't know if it's social media, because the evidence is all correlational and the correlations are really small." For example, Derek Thompson, one of my favorite data-oriented journalists, wrote a widely read essay in The Atlantic on the multiplicity of possible causes. In a section titled Why is it so hard to prove that social media and smartphones are destroying teen mental health? he noted that "the academic literature on social media's harms is complicated" and he then quoted one of the main academics studying the issue—Jeff Hancock, of Stanford University: "There's been absolutely hundreds of [social-media and mental-health] studies, almost all showing pretty small effects."

In this post, I will show that Thompson's skepticism was justified in 2019 but is not justified in 2023. A lot of new work has been published since 2019, and there has been a recent and surprising convergence among the leading opponents in the debate (including Hancock and me). There is now a great deal of evidence that social media is a substantial cause, not just a tiny correlate, of depression and anxiety, and therefore of behaviors related to depression and anxiety, including self-harm and suicide.

First, I must offer two stage-setting comments:

Social media is not the only cause; my larger story is about the rewiring of childhood that began in the 1990s and accelerated in the early 2010s.

I'm a social psychologist who is always wary of one-factor explanations for complex social phenomena. In The Coddling of the American Mind, Greg Lukianoff and I showed that there were six interwoven threads that produced the explosion of unwisdom that hit American universities in 2015, one of which was the rise of anxiety and depression in Gen Z (those born in and after 1996); a second was the vast overprotection of children that began in the 1990s.

In the book I'm now writing (The Anxious Generation) I show that these two threads are both essential for understanding why teen mental health collapsed in the 2010s. In brief, it's the transition from a play-based childhood involving a lot of risky unsupervised play, which is essential for overcoming fear and fragility, to a phone-based childhood which blocks normal human development by taking time away from sleep, play, and in-person socializing, as well as causing addiction and drowning kids in social comparisons they can't win. So this is not a one-factor story, and in future posts I'll show my research on play. But today's post is about what I believe to be the largest single factor and the only one that can explain why the epidemic started so suddenly, around 2012, in multiple countries.

The empirical debate has focused on the size of the dose-response effect for individuals, yet much and perhaps most of the action is in the emergent network effects.

Once you appreciate the extent to which childhood has been transformed by smartphones and social media, you can see why it's a mistake to focus so narrowly on individual-level effects. Nearly all of the research––the "hundreds of studies" that Hancock referred to––have treated social media as if it were like sugar consumption. The basic question has been: how sick do individuals get as a function of how much sugar they consume? What does the curve look like when you graph illness on the Y axis as a function of daily dosage on the X axis? This is a common and proper approach in medical research, where effects are primarily studied at the individual level and our objective is to know the size of the "dose-response relationship." (Although even in medicine, there are important network effects.)

But social media is very different because it transforms social life for everyone, even for those who don't use social media, whereas sugar consumption just harms the consumer. To see why this difference matters, imagine that in 2011, just before the epidemic began, a 12-year-old girl was given an iPhone 4 (the first with a front-facing camera) and began to spend 5 hours a day taking and editing selfies, posting them on Instagram (which had launched the year before), and scrolling through hundreds of posts from others. This was at a time when none of her friends in 7th grade had a smartphone or any social media accounts. Suppose that Instagram does cause anxiety disorders in a dose-response way, but the size of the correlation with anxiety is smaller than the correlation of social isolation with anxiety. The girl spending 5 hours a day on Instagram finds her mental health declining, but her friends' mental health is unchanged. We find a clear dose-response effect. If she were to quit Instagram, would her mental health improve? Yes.

But now fast forward to 2015, when most girls are on Instagram and all teens are spending far less time with their friends in person (as I showed in my Feb 16 post). Most social activity is now asynchronous—channeled through posts, comments, and emojis on Instagram, Snapchat, and a few other platforms. Childhood has been rewired—it has become phone-based—and rates of anxiety and depression are soaring (as I showed in my Feb 8 post). Suppose that in 2015, a 12-year-old girl decided to quit all social media platforms. Would her mental health improve? Not necessarily.

If all of her friends continued to spend 5 hours a day on the various platforms then she'd find it difficult to stay in touch with them. She'd be out of the loop and socially isolated. If the isolation effect is larger than the dose-response effect, then her mental health might even get worse. When we look across thousands of girls, we might find no strong or clear correlation between time on social media and level of mental disorder. We might even find that the non-users are more depressed and anxious than the moderate users (which some studies do find, known as the Goldilocks effect).

What we see in this second case is that social media creates a cohort effect: something that happened to a whole cohort of young people, including those who don't use social media. It also creates a trap—a collective action problem—for girls and for parents. Each girl might be worse off quitting Instagram even though all girls would be better off if everyone quit.

An implication of this analysis is that the correlations we are about to look at probably underestimate the true effect of social media as a cause of the teen mental illness epidemic. But OK, let's take a look.

1. The State of the Art in 2019

In The Coddling of the American Mind, Greg Lukianoff and I tried to explain what happened to Gen Z. We focused on overprotection ("coddling"), but in our chapter on anxiety, we included six pages discussing the possible role of social media, drawing heavily on Jean Twenge's work in her book iGen. The evidence back in 2017, when we were writing, was mixed, so we were appropriately careful, ending the section with this:

We don't want to create a moral panic and frighten parents into banning all devices until their kids turn twenty-one. These are complicated issues, and much more research is needed.

Our book came out in September 2018. Four months later, two researchers at Oxford University—Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski—published a study that was widely hailed as the most authoritative study on the matter. It was titled The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. The study used an advanced statistical technique called "Specification Curve Analysis" on three very large data sets in which teens in the US and UK reported their "digital media use" and answered questions related to mental health. Orben and Przybylski reported that the average regression coefficient (using screen time use to predict positive mental health) was negative but tiny, indicating a level of harmfulness so close to zero that it was roughly the same size as they found (in the same datasets) for the association of mental health with "eating potatoes" or "wearing eyeglasses." The relationships were equivalent to correlation coefficients less than r = .05 (where r = 1.0 indicates a perfect correlation and r = 0 indicates absolutely no relationship). The authors concluded that "these effects are too small to warrant policy change."

It is impossible to overstate the influence of Orben & Przybylski (2019) on journalists and researchers. The comparison to potatoes was vivid and memorable. Here's one writeup of the study:

Whenever you hear a journalist or researcher say that social media has been found to have little or no relationship with mental illness, you're likely to find a link to that study. When I first read the study, I began to have doubts myself. After all, it was the largest and most impressive study ever done on the question, and it was published by researchers who had been studying social media far longer than I had. Might Greg and I have gotten it wrong? Might we have been contributing to yet one more unjustified moral panic over technology?

2. The Social Media and Mental Health Collaborative Review Doc

Many other studies came out in 2019, yielding conclusions on both sides of the question. It was a confusing time. So I decided to compile in one Google doc all the relevant studies I could find. I invited Jean Twenge to join me on the project since she was far more knowledgeable about the various datasets. We posted the Google doc online in February 2019 and invited comments from critics and the broader research community. Each section ends with a request to tell us what we have missed. One of the first comments we got was that some researchers doubted that the mental illness epidemic was real. That led us to create a second Google doc titled: Adolescent mood disorders since 2010: A collaborative review. (I described it in my Feb. 8 Substack post.)

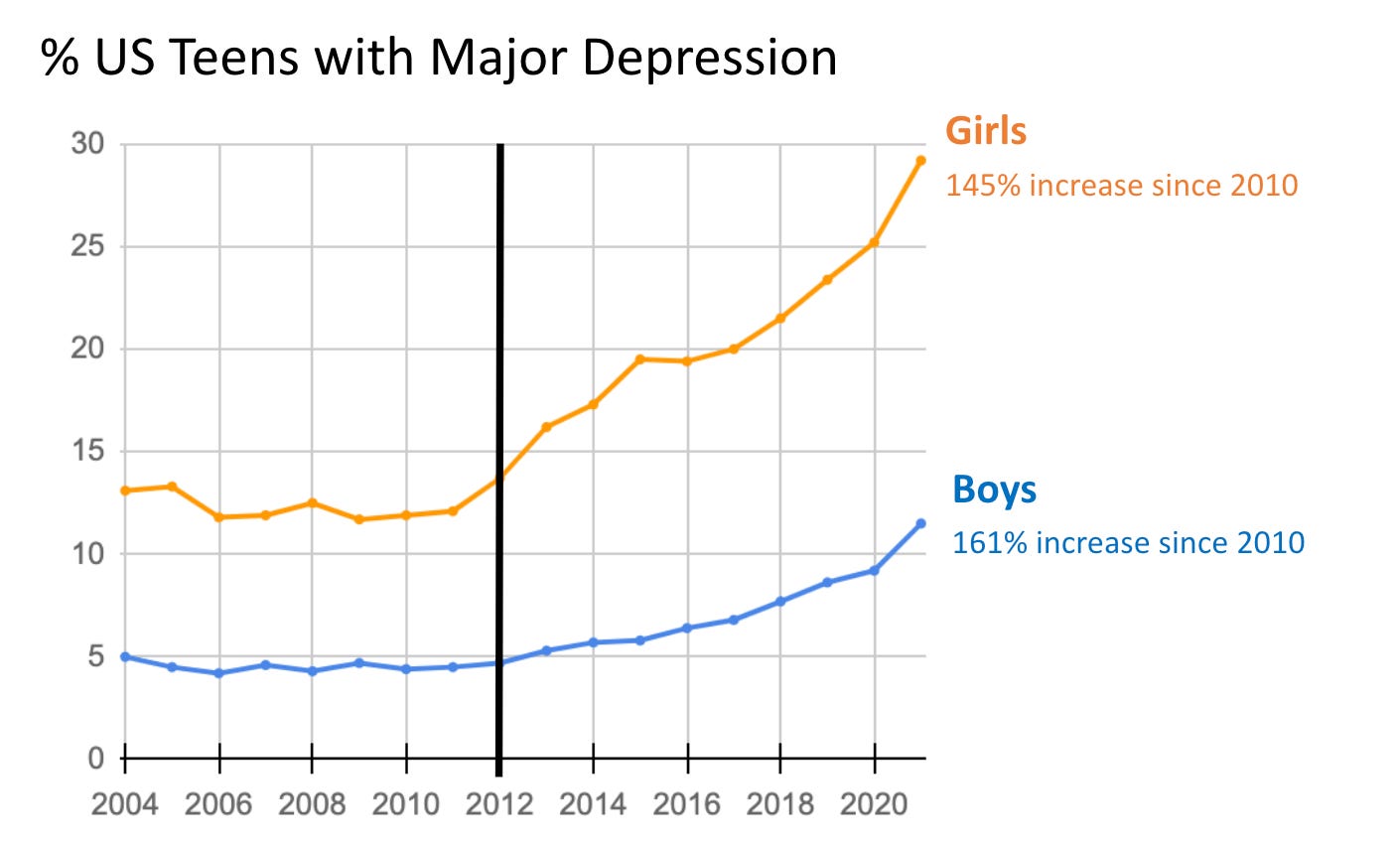

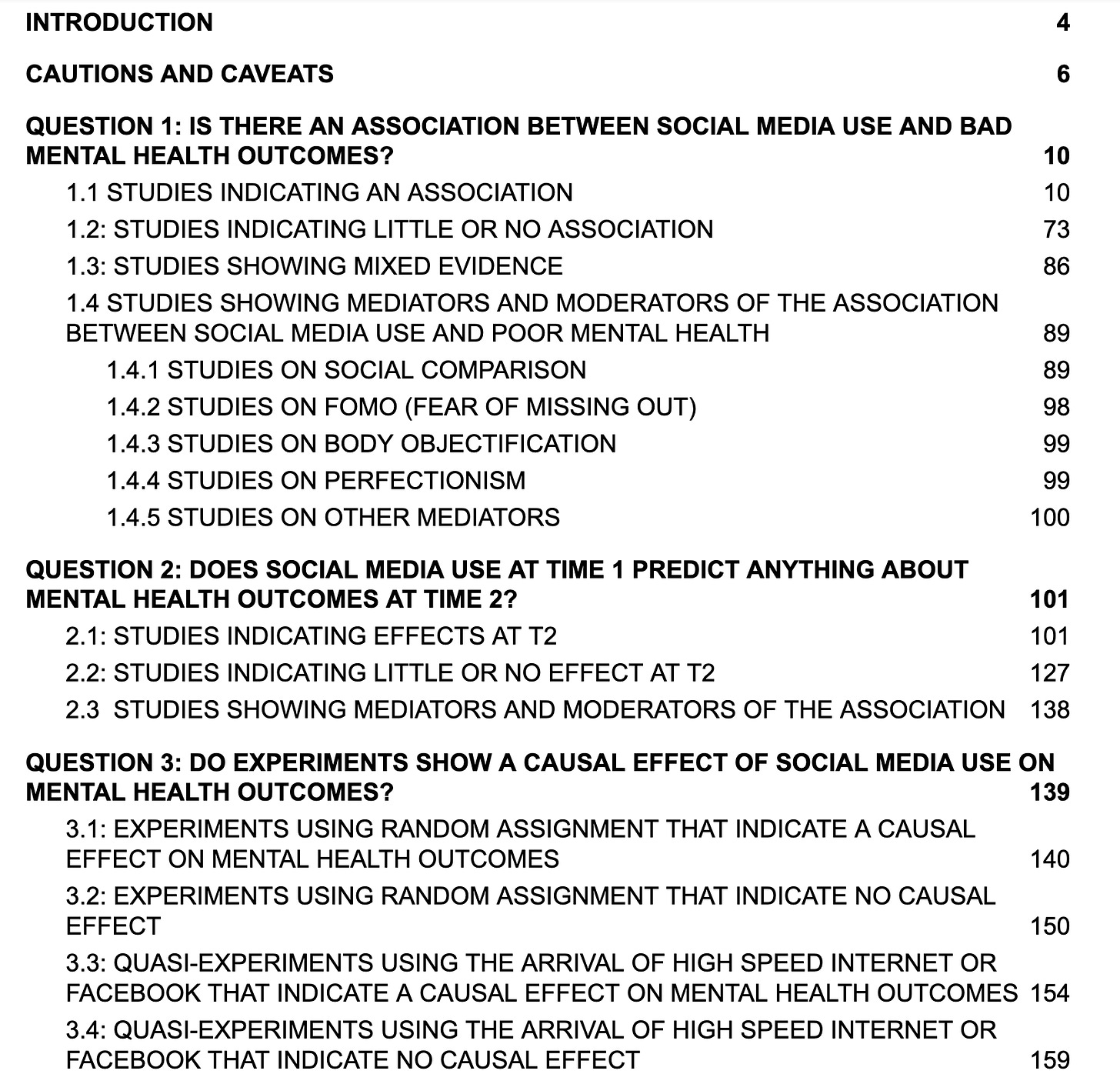

We immediately found that there was a simple and obvious structure for the social media literature review: nearly all of the published studies fell into one of three categories: correlational, longitudinal, or experimental. We therefore structured the document around the three questions addressed by studies of those types. You can see the three questions in the Table of Contents. I've reproduced the first part of it in Figure 1. Please check out the doc itself, and especially our list of "cautions and caveats."

Figure 1. The first part of the Table of Contents of the Social Media and Mental Health Collaborative Review.

In the next four sections of this post, I'll briefly summarize what we've found about causality from those three kinds of studies (with the experiments section divided into two subtypes).

3. Question 1: Is There an Association Between Social Media Use and Bad Mental Health Outcomes?

3.1 Overview

The typical study here asked hundreds or thousands of adolescents to report how much time they spend on social media, or digital media more generally, and then report something about their mental health. Of course, correlational studies can't prove causation, but they are a first step; they tell us what goes with what, and then we can figure out which way the causal arrows go later.

The great majority of studies find a positive correlation between time on social media and mental health problems, especially mood disorders (depression and anxiety). At present, there are 55 studies listed in our review that found a significant correlation, and 11 that found no relationship, or nearly no relationship. The "winning side" is not determined by a simple count, as we explain in the "cautions and caveats" section. But the correlations are widely found and they are not randomly distributed. In fact, there is a revealing pattern found across many studies and literature reviews: Those that look at all screen-based activities (including television) for all kids (including boys) generally find only small correlations (usually less than r = .10), but as you zoom in on social media for girls the correlations rise, sometimes to r = .20, which is quite substantial, as I'll show in a moment.

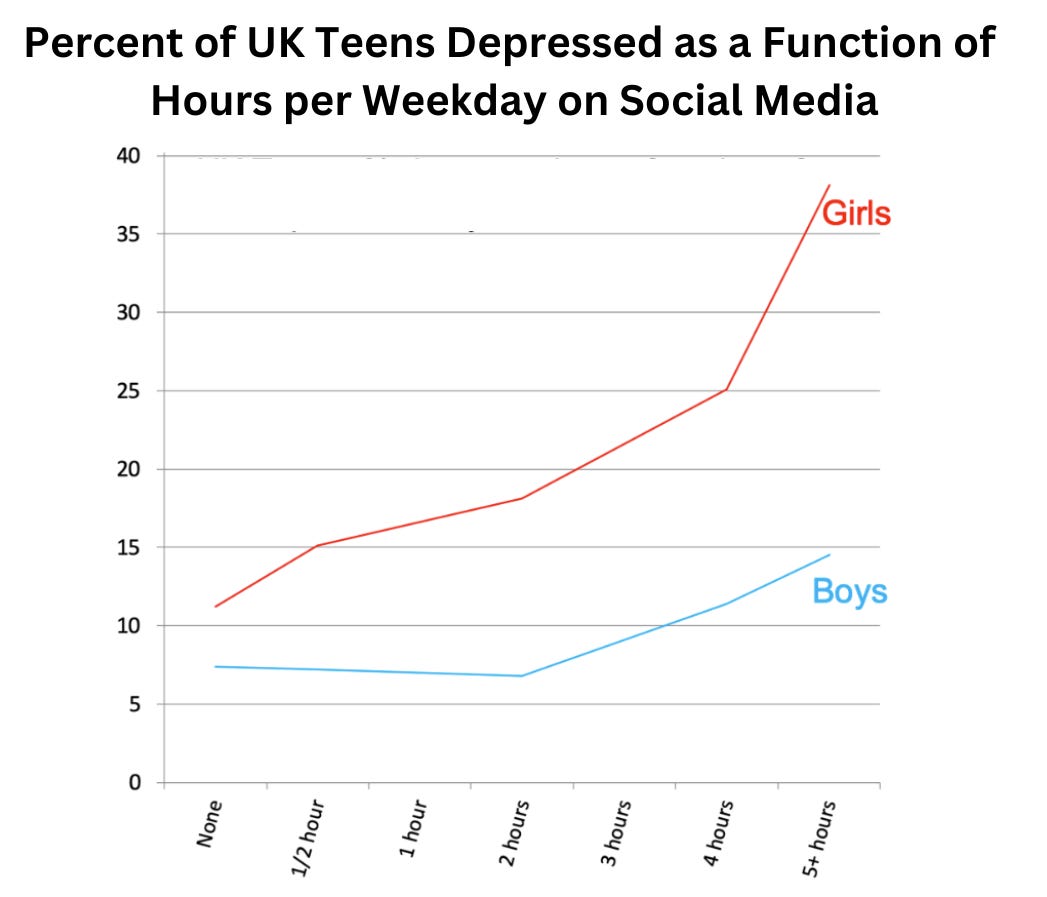

The general finding in these correlational studies is a dose-response relationship such as the one in Figure 2, from Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker, & Sacker (2019) [Study 1.1.5 in the Review doc] who analyzed data from the large Millennium Cohort Study in the UK, which followed roughly 19,000 British children born around the year 2000 as they matured through adolescence.

Figure 2. Percent of UK adolescents with "clinically relevant depressive symptoms" by hours per weekday of social media use, including controls. Haidt and Twenge created this graph from the data given in Table 2 of Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker, & Sacker (2019), page 6.

Note three features of figure 2 that are common across many studies:

The rates of mood disorders are higher for girls than boys.

The lines are curved: moderate users are often no worse off than non-users, but as we move into heavy use, the lines rise more quickly.

The dose-response effect is larger for girls. For boys, moving from 0 to 5 hours of daily use is associated with a doubling of depression rates. For girls, it's associated with a tripling.

3.2 How Can We Square This Large Dose-Response Effect With the "Potatoes" Finding?

How can this large effect of social media use on girls be reconciled with the Orben and Przybylski study, which also examined the same UK dataset?

Twenge and I argued in a published response paper in the same journal that Orben and Przybylski made 6 analytical choices, each one defensible, that collectively ended up reducing the statistical relationship and obscuring a more substantial association. The first issue to note is that the "potatoes" comparison was what they reported for all "digital media use," not for social media use specifically. Digital media includes all screen-based activities, including watching TV or Netflix videos, which routinely turn out (in correlational studies) to be less harmful than social media. In their own published report, when you zoom in on "social media," the relationship is between 2 and 6 times larger than for "digital media." Also crucial is that Orben and Przybylski combined all teens (boys and girls), while many studies have found that the correlations with mood disorders are larger for girls. So even if the association is weak for all kids using all screens, the association is much larger if you zoom in on girls using social media. (You can read Orben and Przybylski's response to our response here.)

Twenge and I later re-ran Orben and Przybylski's SCA on the same datasets (teaming up with researchers Kevin Cummins and Jimmy Lozano.) When we used Orben and Przybylski's assumptions, we replicated their results exactly, obtaining associations that were equivalent to correlation coefficients less than r = .05. But when we limited the analysis to social media for girls, we found relationships that were many times larger, equivalent to correlation coefficients of roughly r = .20.1

3.3 A Surprising Convergence on the Size of the Association

Despite several years of heated debate, a consensus has emerged about just how large the correlation is between social media use and mood disorders. Amy Orben herself conducted a "narrative review" of many other reviews of the academic literature (Orben, 2020; study 5.7 in our review doc). Her conclusion is that "The associations between social media use and well-being therefore range from about r = − 0.15 to r = − 0.10."2 Similarly, Jeff Hancock and his team posted a meta-analysis in 2022, with data that went up through 2018 (Hancock, Liu, Luo & Mieczkowski, 2022, Study 5.27). They report very low associations (near zero) of social media use with some mental health outcomes, but when you zoom in on depression and anxiety as the outcome variables, they too report associations between r = .10 and r = .15.

Both studies (Orben's and Hancock's) merged boys and girls together, and there is a consensus that the relationships are tighter for girls; see Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker, & Sacker (2019), Nesi & Prinstein (2015), and Twenge (2020). So we're reaching a consensus that for girls the true value is north of r = .15, which is consistent with the values around .20 that Twenge, Lozano, Cummins and I found in our SCA paper. This range of values, from r = .15 to r = .20, is quite large when we're talking about health effects found in large datasets, as I explain in this geeky footnote.3 It is much larger than the correlation between childhood exposure to lead and adult IQ (which was found to be around r = .11). And it is certainly much larger than the correlation between mood disorders and eating potatoes or wearing glasses.

In fact, in our SCA paper, we compared the association of social media time with mental illness to other variables found in the same datasets. In that same UK dataset, mood disorders were more closely associated with social media usage than with marijuana use and binge drinking, though less closely associated with sleep deprivation. I'm not saying that a day of social media use is worse for girls than a day of binge drinking. I'm just saying that if we're going to play the game of looking through lists of correlations, the proper comparison is not potatoes and eyeglasses, it is marijuana use and binge drinking.

To conclude this section: Few parents would knowingly let their daughters become heavy users of anything that was correlated r = .20 with mental illness (again, see Figure 2). The effects might be even larger for younger teen girls, who are just beginning puberty, according to a recent study by Orben, Przybylski, Blakemore, & Kievit (2022). Granted, these correlations don't prove causation, but the frequent finding that the correlations are consistently higher for social media, and higher for girls, tells us that we're not just looking at random noise here. There is a consistent story emerging from these hundreds of correlational studies.

What would it take to show that social media use was causing teen girls to become depressed and anxious? Social scientists generally move on from correlational studies to longitudinal studies and true experiments.

Share After Babel

4. Question 2: Does Social Media Use at Time 1 Predict Anything About Mental Health at Time 2?

The second group of studies is known as longitudinal studies, in which hundreds or thousands of people are tracked over some time period and measured repeatedly. Typically, participants fill out the same survey once per year, allowing researchers to measure change over time in the same research participants. But these studies have an interesting property that allows researchers to infer causality; you can look to see if an increase or decrease in some behavior at one point in time predicts a change in other variables at the next measurement time. For example, let's say a teen reports that she spends two hours a day on social media, on average, across a 10-week study. If in week 3 she suddenly reduces her time to zero, what do we expect to happen to her mood in week four? Will she be happier or sadder? If there is, on average, a change in happiness the week after people quit or reduce their social media time, then we can infer that the change in mood was caused by the change in behavior the prior week.

So what do we find in these studies? As I write this post in Feb. 2023, we have 40 longitudinal studies in section 2 of the Collaborative Review doc. Twenty-five of them (62.5%) found evidence indicating causation, and 15 of them largely failed to find such evidence. Once again, you can't just count up the studies and let the majority side win; studies that fail to find an effect are sometimes harder to publish. But our collaborative review docs make it easy to acquaint yourself with the range of studies and see what differentiates the studies that found evidence of harmful effects from those that did not. As we read through the studies in sections 2.1 and 2.2, we noticed something: the studies that used a short time interval (a week or less between measurements) mostly failed to find an effect, which makes sense if social media is addictive, as much evidence suggests. Going cold turkey doesn't make you happy, it makes you anxious and dysphoric for a few weeks, so we should not expect to find benefits to mental health in the short-interval studies.

Zach Rausch (the lead researcher for this Substack) created a 2x2 table to categorize all the studies in section 2 as either a short interval (a week or less) or long interval (a month or more), and as finding an effect versus no effect. He found that 7 studies used a week or less (5 of them were daily), and only 1 of the 7 found an effect. But 33 studies used a month or more (20 were annual) and of these, 24 found a significant effect. So a simple dose-response model in which social media is like poison (where cutting consumption on Monday makes you feel better on Tuesday) does not seem to be supported. But 73% of the studies that looked for causal effects a month or more in the future found them.

Leave a comment

5. Question 3A: Do Experiments Using Random Assignment Show a Causal Effect of Social Media Use on Mental Health?

Now we come to the gold standard in the social sciences for testing causality: the experiment. Initially, we included all experiments in this section, but in the last year, several "quasi-experiments" that took advantage of natural variation have been published. I'll cover those in the next section. In this one, we'll just look at true experiments, in which participants were randomly assigned to either a treatment condition or a control condition, and then some dependent variable related to mental health was measured. Most experiments are done on college students or young adults—it's hard to get parental consent to do experiments on minors—so we did not limit this section to studies on adolescents. There are few experiments out there (compared to correlational and longitudinal studies), so we included some that used adults if it was clear that many or most were relatively young.

In Feb. 2023 we have 18 true experiments in Section 3, of which 12 (67%) found evidence of a causal effect (Section 3.1) and 6 failed to find evidence of a causal effect (section 3.2). Some of the studies randomly assigned college students or young adults to reduce their social media use for a while and then measured self-reported mental health outcomes, compared to the control group which was instructed to make no changes. For example, Hunt, Marx, Lipson & Young (2018) randomly assigned college students to greatly reduce the use of social media platforms (or not reduce) and then measured their depressive symptoms four weeks later. They found that "The limited use group showed significant reductions in loneliness and depression over three weeks compared to the control group."

Some of the studies exposed girls and young women to time on Instagram, or to experiences designed to mimic Instagram, and then looked at the psychological aftereffects. For example, Kleemans, Daalmans, Carbaat, & Anschütz (2018) randomly assigned teen girls to be exposed either to original selfies taken from Instagram or to selfies that were manipulated to be extra attractive. "Results showed that exposure to manipulated Instagram photos directly led to lower body image." Engeln, Loach, Imundo, & Zola (2020) randomly assigned female college students to use Facebook, use Instagram, or perform an emotionally neutral task (the control condition) on an iPad. The finding: "Those who used Instagram, but not Facebook, showed decreased body satisfaction, decreased positive affect, and increased negative affect."

Turning to the six experiments that failed to find significant effects, it is noteworthy that four of these six experiments involved asking participants to reduce or eliminate social media for one week or less. As we saw in the examination of longitudinal studies, going "cold turkey" brings immediate discomfort to addicts; the benefits only kick in after a few weeks when the brain has adapted to the loss of chronic stimulation. So if we remove all of the studies that used a week or less (including two studies in section 3.1 that found an effect), the final tally becomes ten that found evidence that social media is harmful (80%) and two that did not.

In sum, there are now many true experiments using a variety of methods to test questions such as whether reducing or eliminating exposure to social media confers benefits (it does, when continued for at least a month), or if exposing girls and women to Instagram or Instagram-like experiences damages their mood or body image (it does). These experiments provide direct evidence that social media—particularly Instagram—is a cause, not just a correlate, of bad mental health, especially in teen girls and young women.

Leave a comment

6. Question 3B: Do Quasi-experiments Using the Arrival of Facebook or High-speed Internet Show a Causal Effect of Social Media Access on Mental Health?

The previous three questions all asked about individual-level effects: what happens to individuals who are exposed to more or less social media? But this fourth category of studies is different—and very important—for this reason: it is the only one that allows us to look at emergent network effects. These studies look at how whole communities changed when social media suddenly became much more available in that community. These studies are sometimes called "quasi-experiments" because the researchers take advantage of natural variation in the world as though it was random assignment.

For example, Braghieri, Levy, & Makarin (2022) took advantage of the fact that Facebook was originally offered only to students at a small number of colleges. As the company expanded to new colleges, did mental health change in the following year or two at those institutions, compared to colleges where students did not yet have access to Facebook? Yes, it got worse. The authors say:

We find that the roll-out of Facebook at a college increased symptoms of poor mental health, especially depression, and led to increased utilization of mental healthcare services. We also find that, according to the students' reports, the decline in mental health translated into worse academic performance. Additional evidence on mechanisms suggests the results are due to Facebook fostering unfavorable social comparisons.

We also found five studies that used a similar design applied to the rollout of high-speed internet. It's hard to have a phone-based childhood when data speeds are very low. So what happened in Spain as fiber optic cables were laid and high-speed internet came to different regions at different times? Same thing, except with clearer evidence of a gendered effect. Arenas-Arroyo, Fernandez-Kranz, & Nollenberger (2022; study 3.3.2) analyzed "the effect of access to high-speed Internet (HSI) on hospital discharge diagnoses of behavioral and mental health cases among adolescents." Their conclusion:

We find a positive and significant impact on girls but not on boys. Exploring the mechanism behind these effects, we show that HSI increases addictive Internet use and significantly decreases time spent sleeping, doing homework, and socializing with family and friends. Girls again power all these effects.

They found that the arrival of high-speed internet had a particularly damaging effect on the quality of father-daughter relationships.

Guo (working paper, 3.3.1) did a similar study in British Columbia, Canada, where it took a long time for high-speed internet to reach rural areas. She found similar gendered effects:

Estimates suggest high-speed wireless internet significantly increased teen girls' mental health diagnoses — by 90% — relative to teen boys over the period when visual social media became dominant among teenagers. I find similar effects across all subgroups, indicating they are not driven by differences in confounding characteristics.

Guo's study also verified that the arrival of high-speed wireless in each town was accompanied by an increase in interest in social media.

In sum, we found six quasi-experiments that looked at real-world outcomes in real-world settings when the arrival of Facebook or high-speed internet created large and sudden emergent network effects. All six found that when social life moves rapidly online, mental health declines, especially for girls. Not one study failed to find a harmful effect.

7. Conclusion: Social Media Is a Major Cause of Mental Illness in Girls, Not Just a Tiny Correlate

We are now 11 years into the largest epidemic of teen mental illness on record. As the CDC's recent report showed, most girls are suffering, and nearly a third have seriously considered suicide. Why is this happening, and why did it start so suddenly around 2012?4

It's not because of the Global Financial Crisis. Why would that hit younger teen girls hardest? Why would teen mental illness rise throughout the 2010s as the American economy got better and better? Why did a measure of loneliness at school go up around the world only after 2012, as the global economy got better and better? (See Twenge et al. 2021). And why would the epidemic hit Canadian girls just as hard when Canada didn't have much of a crisis?

It's not because of the 9/11 attacks, wars in the middle east, or school shootings. As Emile Durkheim showed long ago, people in Western societies don't kill themselves because of wars or collective threats; they kill themselves when they feel isolated and alone. Also, why would American tragedies cause the epidemic to start at the same time among Canadian and British girls?

There is one giant, obvious, international, and gendered cause: Social media. Instagram was founded in 2010. The iPhone 4 was released then too—the first smartphone with a front-facing camera. In 2012 Facebook bought Instagram, and that's the year that its user base exploded. By 2015, it was becoming normal for 12-year-old girls to spend hours each day taking selfies, editing selfies, and posting them for friends, enemies, and strangers to comment on, while also spending hours each day scrolling through photos of other girls and fabulously wealthy female celebrities with (seemingly) vastly superior bodies and lives. The hours girls spent each day on Instagram were taken from sleep, exercise, and time with friends and family. What did we think would happen to them?

The Collaborative Review doc that Jean Twenge, Zach Rausch and I have put together collects more than a hundred correlational, longitudinal, and experimental studies, on both sides of the question. Taken as a whole, it shows strong and clear evidence of causation, not just correlation. There are surely other contributing causes, but the Collaborative Review doc points strongly to this conclusion: Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic in Teen Girls.

Addendum, April 19 2023: Here are the published critiques I have found from fellow researchers who disagree with my conclusions.

Don't panic about social media harming your child's mental health – the evidence is weak. By Stuart Ritchie

"Some" Are Misrepresenting CDC Report Findings Specific To The Use Of Social Media & Technology By Youth. By The White Hatter

Why I'm Skeptical About the Link Between Social Media and Mental Health. By Dylan Selterman

The Statistically Flawed Evidence That Social Media Is Causing the Teen Mental Health Crisis, by my NYU colleague Aaron Brown, at Reason.com.

Here is my response (published on April 17, 2023): Why Some Researchers Think I Am Wrong About Social Media and Mental Illness

Addendum August 9, 2023: David Stein's substack The Shores of Academia is offering a series of helpful critiques of my work. In Social Media and Time Displacement he critiques this post and makes the valid points that I do not provide evidence that tween girls are spending so much time on social media (5 hours a day is surely well above average, even if you include time not ON the app but thinking about it or taking photos, which I did). He also correctly notes that I have not defined terms, or concentrated enough on all the other screen-based activities that tweens and teens are doing. I am drawing on Stein's critiques to improve the story in The Anxious Generation.

Footnotes:

1There was one other difference that turned out to make a large difference in our results. Orben and Przybylski had not only controlled for demographic variables (such as race and parents' educational levels, which is universally done); they also controlled for some psychological variables that are potential mediators of a relationship between social media usage and poor mental health, such as negative attitudes about school and closeness with parents. We found that controlling for these psychological variables heavily suppressed the relationship between social media use and poor mental health.

2The correlations are negative because she framed this as "well-being"; they are positive if we talk about mental illness.

3Many researchers learned in graduate school that a correlation coefficient of r = .5 and above is a "large" correlation, r = .3 and above is a "medium" sized correlation, and r = .10 and above is a "small" correlation, with r < .10 being trivial, not even "small." But recently, psychologists have noted that these cutoffs make no sense; what counts as large or small varies by domain. The key paper here is Gotz, Gosling, and Rentfrow (2020). Small Effects: The Indispensable Foundation for a Cumulative Psychological Science. The authors note that in the domains of public health and education, many of the things that warrant public expenditure are correlated with outcomes in the ballpark of r = .05 to r = .15. For example, Gotz et al. note that the correlation of calcium intake and bone mass in pre-menopausal women is r = .08, which is enough to recommend that women take calcium supplements. The correlation between childhood lead exposure and adult IQ is r = .11, which is enough to justify a national campaign to remove lead from water supplies. These correlations are smaller than the links between mood disorders and social media use for girls. Gotz et al. note that such putatively "small" effects can have a very large impact on public health when we are examining "effects that accumulate over time and at scale", such as millions of teens spending 20 hours per week, every week for many years, trying to perfect their Instagram profiles while scrolling through the even-more-perfect profiles of other teens.